Above: Masai giraffe in Tanzania

Jessica Manzak, North Carolina Zoo Tanzania Giraffe Research Program Coordinator

Tanzania just doesn’t look the same from behind a computer screen, even though the screen is filled with pictures of giraffes. Between the intense rains and flooding, and now the COVID-19 lock downs, I’m spending more time in the office, analyzing the photos that were taken during last year’s surveys of giraffe populations in southern Tanzania. While I’m going through the photos, I come across some from my favorite giraffe, Homeboy. I met Homeboy for the first time during wet season surveys last year.

Above: Homeboy, a favorite giraffe

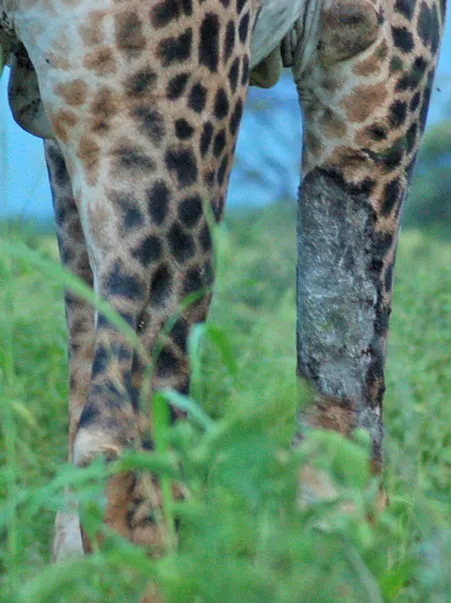

Left: The mysterious giraffe skin disease

Homeboy has a problem, though. Giraffe are in trouble as populations have declined by close to 50% since the 1970’s. A number of factors have driven this decline, including habitat loss and fragmentation, illegal hunting of giraffe for bushmeat in some areas, and health issues. Homeboy’s problem, like close to 90% of adult Masai giraffe in Ruaha National Park, is Giraffe Skin Disease, an emerging and little understood disease. In Ruaha, the disease affects the inside and backs of the front legs. Giraffe affected by the disease have wrinkled, crusted, and hairless gray or black patches of skin on one or both front legs. Giraffe in other countries, and even some zoos outside of Africa, have other versions of this skin disease that occurs on different parts of the body, like the neck and chest. And for now, that’s about all we know for sure about the disease. We don’t know what causes it, or even if it’s the same cause for all the variations that are seen. We don’t know how it spreads to affect new giraffe. We don’t know how fast it progresses, or if it affects a giraffe’s ability to walk, reproduce, or escape from predators.

Giraffe Skin Disease isn’t the only area where we’re lacking information about Masai giraffe populations. In Selous Game Reserve, also in southern Tanzania and one of the largest protected areas in the world, a new hydroelectric dam is being constructed, along with roads and power lines to access the site and bring power out to the nation. Around 143,000 hectares of land are being cleared of timber in preparation for this project, and no one quite knows how this will affect the wildlife. Furthermore, in southern Tanzania, the only giraffe census information comes from aerial surveys, which can be unreliable as most areas are heavily wooded. This means we don’t have a good breakdown of the demographics (how many females versus males, and how many adults or calves) in these areas, something which could help to monitor the health of the overall population.

Last year, Tanzanian government agencies involved in wildlife research, management, and protection developed a National Giraffe Conservation Action Plan, and North Carolina Zoo was invited to participate. The plan identified areas of priority conservation needs for giraffe in Tanzania and worked to determine ways to address those needs. Some of the top needs identified were good demographic data and understanding the threats facing Tanzania’s national animal, the Masai giraffe. That’s where North Carolina Zoo comes in. We’re working in Ruaha National Park to better understand the effects of skin disease on the giraffe populations here, and in Selous Game Reserve to monitor the effects of the construction projects and bushmeat hunting.

Above: Masai giraffe getting a drink of water

Thanks to some new technologies, we have a way to keep track of individual giraffe in these areas. Similar to facial recognition software, there is now software that lets us identify the unique spot pattern of each giraffe. Collecting photos of the giraffe will let us build a database of all the individuals in each protected area. When we see the same individual again at a later date, we can compare the severity of the skin disease on that individual over time. We can also track their reproductive success, by noting when they are lactating, observed breeding, and recording and comparing the number of calves across years. In Selous, being able to keep a close eye on the population numbers, as well as how many individuals are re-sighted in future surveys, will help us gauge the effects of the construction on the populations. North Carolina Zoo hopes to keep the demographics portion of the surveys going long term, so in the future we’ll have enough data to be able to spot trends in population changes and be able to help Tanzanian protected area management authorities make appropriate management changes in time to respond to threats as they emerge. But for now, as we compile photos for our database, we’re all just Seeing Spots in Tanzania.