Written by Kevin Langergraber, Co-Director of the Ngogo Chimpanzee Project and Associate Professor, Arizona State University

In Uganda, Kibale National Park contains one of the largest chimpanzee populations in East Africa, making it one of the few remaining strongholds for chimpanzees in the wild. However, Kibale’s chimpanzees are threatened by illegal hunting and often get caught in snares set by poachers. To protect the chimpanzees and other animals in Kibale, teams began conducting regular snare removal patrols in 2010. The project is called the Ngogo Chimpanzee Project and consists of local Ugandans, some of whom are ex-poachers themselves.

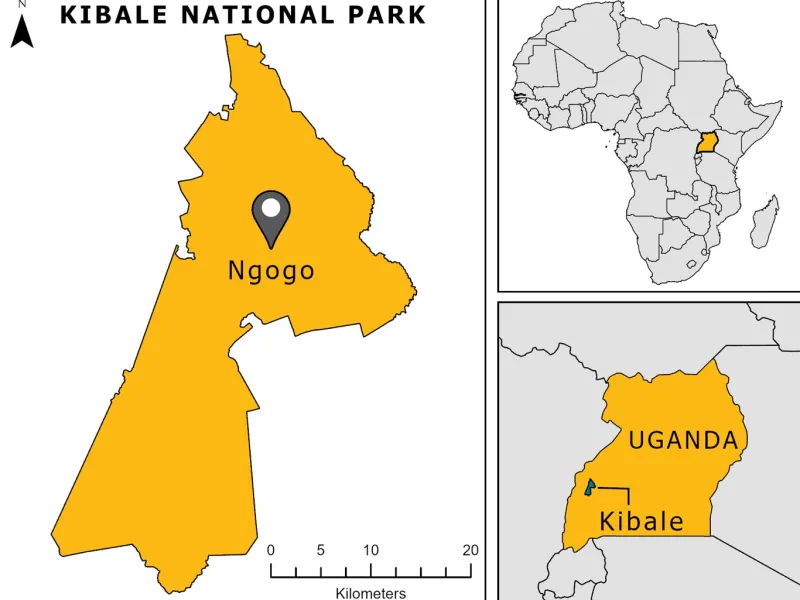

Map showing where the Ngogo chimp community is within Kibale National Park, Uganda

Working alongside Uganda Wildlife Authority Rangers, they conduct multi-day patrols, spend up to six nights camping overnight in the forest, and look for signs of poachers that will lead them to snares. The North Carolina Zoo supports the project by providing them with hardware such as mobile devices and laptops for anti-poaching patrols using SMART (Spatial Monitoring and Reporting Tool) technology, trained their staff on its use, and have provided technical support. The project has made significant progress and now employs five dedicated snare teams that patrol every square foot of Kibale to protect the park’s chimpanzees and other wildlife.

Ngogo Chimpanzee Project snare removal team members

There is a very high-density human population living all around Kibale National Park, which makes even low levels of hunting unsustainable for the many species of threatened and endangered animals that live there. While people in this area of Uganda generally do not hunt chimpanzees and other primates due to local taboos, chimpanzees often get caught in snares that are set for other animals, such as giant forest hogs, bushpigs, and duikers (a type of forest antelope).

Snares consist of loops of wire that are attached to small saplings that are bent over to store kinetic energy. When an animal steps in a shallow hole in the ground where the snare is set, it sets a trigger that releases the bent-over sapling, constricting the snare tightly around the animal’s limb. While smaller animals cannot escape from the snare and sapling, chimpanzees can usually break the wire snare off the sapling to escape the area. However, they often cannot remove the wire snare itself from their limb, as snares are made of metal wire that digs deep into the flesh and can’t be broken through biting. Many chimpanzees in Kibale have snare injuries, including missing hands and feet. From remote camera traps set up across Kibale, we also know that snares can lead to severed trunks in elephants, depriving them of a critical feeding tool.

A chimp called Carter, part of the Ngogo chimp community

The best way to prevent snare injuries is to reduce hunting pressure by removing as many as possible. Despite our best efforts at this, however, even the Ngogo community of chimpanzees, who are better protected than other chimpanzees in Kibale because researchers monitor and study them year-round, fall victim to snaring injuries. In an upcoming blog post, Ngogo Chimpanzee Project researcher Aaron Sandel will tell the story of how we intervened to remove a snare from an adult male Ngogo chimpanzee named Garrett.